One Japanese-to-English Translator's Path into the World of TranslationThere are as many long and winding roads as there are translators.

(April 29, 2022; last updated May 26, 2025)

Executive Summary People follow diverse paths in becoming translators, and many translators travel paths that they never thought would lead to a career as a translator. Here is just the story of one translator who for years was unwittingly doing things to prepare himself to be a Japanese-to-English translator and interpreter. Nothing was planned, nor could it have been.

I am sometimes asked how one becomes a translator. Sometimes the question is from a non-translator; usually it is from someone who has never met a translator. Since I never met a translator of any languages until a few years after becoming one myself, I can hardly blame people for wondering about the whys and the hows of becoming one. I had nobody to answer those questions for me when I was starting out.

I also sometimes hear the question from people learning Japanese in various situations and from people I meet through work.

Seldom, however, do I hear the question from clients. Perhaps some clients think that, just as with other professions, there is some formulaic path that you travel, at the end of which you are a translator. It is certainly not formulaic and often not an easy trip.

Here is a short version of my particular story. It is certainly not typical, and I am not sure there is any "typical" straight path to becoming a translator. Nor do I think that others could—or should—attempt to follow the same path; there are just too many uncontrollable variables in our lives to expect that to work. As such, this account is best understood as just one way one person made the trip. Your mileage and path (including whether or not you will be happy at your destination) will definitely vary.

Here is a short version of my particular story. It is certainly not typical, and I am not sure there is any "typical" straight path to becoming a translator. Nor do I think that others could—or should—attempt to follow the same path; there are just too many uncontrollable variables in our lives to expect that to work. As such, this account is best understood as just one way one person made the trip. Your mileage and path (including whether or not you will be happy at your destination) will definitely vary.

Beginnings

My initial encounters with foreign languages were in high school and university, with German and French, respectively, in the 1960s. I had top grades in both languages, but retain embarrassingly little knowledge of both and am totally incapable of conversing in either.

Russian Language at Defense Language Institute (DLI) in Monterey (Mid-1960s)Navy Spook Wannabe in an Army Language School

My next language was Russian, which I had chosen as one of the languages I wished to learn after being told by the US Navy I could learn a foreign language. What we were not told while learning Russian at DLI is what we would actually be doing after Russian and a few other schools. The Navy gave us few details of our future assignments until shortly before we headed to our first duty station. Until then, our job was simply to become proficient at Russian.

I graduated very high in my Russian class at DLI and considered myself to be a hot-shot Communications Technician (the job title changing to Cryptologic Technician some years after I left the Navy). I was, in fact, a hot-shot CT. But I retain very little spoken Russian. When you don't actively speak an acquired foreign language, you tend to lose it quite quickly.

We received more than 1500 hours of classroom instruction in Russian at DLI, provided by an interesting cohort of teachers who had defected from the Soviet Union at various times. There were some oldsters from the immediate post-revolutionary period in Russia, some from WW2 or shortly thereafter, and numerous Cold War era defectors. One was the former Commander of the Lithuanian army, Stasys Rastikis.

We received more than 1500 hours of classroom instruction in Russian at DLI, provided by an interesting cohort of teachers who had defected from the Soviet Union at various times. There were some oldsters from the immediate post-revolutionary period in Russia, some from WW2 or shortly thereafter, and numerous Cold War era defectors. One was the former Commander of the Lithuanian army, Stasys Rastikis.  Our classroom work was augmented by an hour or so each night listening to tapes on our reel-to-reel recorders, and by standing in the chow line in the morning mumbling our Russian dialog scripts, either to ourselves or with a classmate playing the part of our dialog partner. It was interesting to hear people do this in nearly a dozen languages before and even at breakfast in the chow hall of a US Army base.

Our classroom work was augmented by an hour or so each night listening to tapes on our reel-to-reel recorders, and by standing in the chow line in the morning mumbling our Russian dialog scripts, either to ourselves or with a classmate playing the part of our dialog partner. It was interesting to hear people do this in nearly a dozen languages before and even at breakfast in the chow hall of a US Army base.

Nobody resented having to study; there was the promise of not having to perform "normal" military duties after getting out of language school. That promise was largely kept.

Another inducement to learning was living in the B5 Russian barracks, where conversation was only permitted in Russian. Once at my duty station in Japan, however, my duties required no spoken Russian, and, for obvious reasons, we had no direct contact with Russian speakers.

Off to See the World and Several Seas (1967—)My First "Japan Experience"

I have never sat in a Japanese language classroom or participated in any formal Japanese-language learning program; I am a total autodidact. While numerous of my "spook" colleagues spent many endless nights drinking in bars that catered to foreigners in Yokohama's Chinatown, I and several like-minded Russian-language spooks shunned that pastime, choosing instead to spend time in what were arguably—and often turned out to be—more uplifting adventures.

We would take what we called 200-Yen train tours. We would buy a 200-Yen train ticket and get off at a random station that a 200-Yen fare would take us to. Train fares being what they were then (the minimum fare being 20 yen on some lines), that easily enabled us to avoid encounters with the English-capable locals near our base and provided a good trial-by-fire of our ability to communicate in Japanese.

To this day, most Japanese are not noted for their conversational English ability; in the 1960s, there were even fewer Japanese capable of conversing—or wanting to converse with foreigners—in English. I combined those trips with hours of self-study of the written language.

That self-study effort to learn the written language was helped along by a cruise to the Indian Ocean. I brought as many Japanese textbooks as I could find with me onto the ship. These included a kanji dictionary by Florence Sakade and several books by Roy Miller. I also brought some Japanese-language weeklies with me as reading material.

That self-study effort to learn the written language was helped along by a cruise to the Indian Ocean. I brought as many Japanese textbooks as I could find with me onto the ship. These included a kanji dictionary by Florence Sakade and several books by Roy Miller. I also brought some Japanese-language weeklies with me as reading material.

Since my mission was communications, and the Russians were unsurprisingly not very talkative late at night, I made good use of my I'm a total autodidact. midnight-to-8am "mid watches" (and most of my other free time) to learn to read and write Japanese.

That cruise took us to, among other places, Malaysia, Diego Garcia (in the middle of the Indian Ocean), Mauritius, and Mozambique. On the way back, we stopped at Perth, Adelaide, and Pago Pago. After returning to Japan, I continued my self-study and my purposeful avoidance of English-capable locals.

Because of the nature of my duties while stationed in Japan, I was required to go through SERE (survival, evasion, resistance, and escape) school, held in California. This involved too many days with nothing to ingest but water and salt, physical punishment from interrogators, and a variety of other unpleasant things designed to teach us what it would be like to be captured by the enemy.

Because of the nature of my duties while stationed in Japan, I was required to go through SERE (survival, evasion, resistance, and escape) school, held in California. This involved too many days with nothing to ingest but water and salt, physical punishment from interrogators, and a variety of other unpleasant things designed to teach us what it would be like to be captured by the enemy.

After my discharge, having been made to swear in writing that I would not visit a communist-bloc country for some years (I forget how many) and having been ceremoniously given a telephone number to call if I was approached by any suspicious persons, I embarked on my post-spook life. Some of us received recruiting letters from the NSA shortly after being discharged, but I had no interest in working in what I suspected would have been a very stifling environment.

Back in the USA: Life after the Spookosphere (1970—)Rehabilitation into Society

I finished studies for and obtained a degree in electrical engineering at Drexel University from Philadelphia at night, while working for nearly five years at the Engineering Research Center of what was then Western Electric, located in Princeton, New Jersey.

I finished studies for and obtained a degree in electrical engineering at Drexel University from Philadelphia at night, while working for nearly five years at the Engineering Research Center of what was then Western Electric, located in Princeton, New Jersey.  Western Electric no longer exists, having been forced by the government to split into a number of separate companies because its parent company controlled too much of the telephone infrastructure. Oldsters might remember that Western Electric, in addition to making telephone equipment, provided the audio technology for many movies and TV programs in the past.

Western Electric no longer exists, having been forced by the government to split into a number of separate companies because its parent company controlled too much of the telephone infrastructure. Oldsters might remember that Western Electric, in addition to making telephone equipment, provided the audio technology for many movies and TV programs in the past.

I did nothing at the research center related to language. After a short period at a related millimeter waveguide pilot plant in Hopewell, I was transferred to a fiber optics laboratory at the main research center in Princeton. Optical fiber was destined to—and did—replace copper cable in landline telephone transmission systems, the only type of phones there were in 1970. I was doing things like pulling thin optical fiber from molten silica preforms and making various tests and measurements of the resulting fiber, such as measuring the fiber's transmission loss and the periodicity of the variations in the fiber diameter, which caused undesirable mode conversion in single-mode fiber. But I digress.

If you are waiting for me to get to my entrance into translation, bear with me; there is a bit more before that.

One day when I was in the lab pulling my fiber, so to speak, I noticed an electronics industry newspaper want ad by a company looking for an electrical engineer who speaks, reads, and writes Japanese and would be willing and able to transfer to Japan.  I said to myself "I'm their man!" and immediately phoned the company, a major manufacturer of electronic test and measuring instruments, from the lab. I was a bit dismayed when they quickly put a native Japanese speaker on the phone with me to check to see if my claims of Japanese ability were valid. I evidently passed muster, because they told me to fly to Seattle to meet them. I was finally to have a position in which Japanese language was not only useful, but actually essential.

I said to myself "I'm their man!" and immediately phoned the company, a major manufacturer of electronic test and measuring instruments, from the lab. I was a bit dismayed when they quickly put a native Japanese speaker on the phone with me to check to see if my claims of Japanese ability were valid. I evidently passed muster, because they told me to fly to Seattle to meet them. I was finally to have a position in which Japanese language was not only useful, but actually essential.

Adventure in Corporate America (1975—)Not that much fun while it lasted

After arriving in the Pacific Northwest, I learned that there were very few applicants who had filled the job requirements. Some were American engineers who said they spoke Japanese but turned out to have been exaggerating or misjudging their language capabilities. Japanese ability is not something you can fake until you make it. Other applicants were fluent in Japanese (they were native Japanese speakers) but were not hired, and I suspected that it was because the company did not want a Japanese person to represent them in Japan, but was later told that it had something to do with government defense contracts and security clearances.

In any event, I spent a few months at the company headquarters in the Seattle area, after which I moved to Yokohama, where I established the Japan branch and headed a team of about ten people. Unwittingly training to survive in translation and interpreting. In the process, we fired our Japanese trading company, then called Toyo Trading (the current TOYO Corporation) and engaged a division of Tokyo Electron as our new partner, with our Japan Branch, which I managed, performing servicing of all our products and doing direct sales of our high-end products, chiefly printed circuit board testers.

I spent several years managing the branch, which provided me valuable opportunities to acquire sales-ready spoken Japanese. Since we were short-handed, I would sometimes need to go out and meet clients by myself. Before I ventured out on these missions alone, however, I spent as much time as possible pairing with my Japanese sales people, one of whom I had poached from our former trading company, and another who previously worked for what would become Advantest (it was Takeda Riken at the time, named for the founder, Takeda Ikuo). I stole everything I could from these guys regarding language and behavior in front of customers.

My translation duties were very limited, being mostly just occasionally providing information to the home office on competing products and companies. At this point, I still did not have an inkling that I would shortly become a career translator.

Bold (?) Migration to the Brave New World of Translation (Late 1978—)Migrating from barter to billing for cash

After several years, I left the company and stayed in Japan. Before I left, however, I had a few tastes of what commercial Japanese-to-English translation was like.

The first was provided by a former salesperson of mine who had quit the branch and started working for a company selling blood pressure gauges (sphygmomanometers). The company had been established by Takeda Ikuo, founder of the above-noted Takeda Riken, after he left that company at the "urging" of the company and a bank that essentially took over Takeda Riken.

My former employee asked if I could translate the user manual for one of their products. I certainly could. What was I paid? Two blood pressure gauges, in barter for the translation. Wait! There must be people out there paying money for translation. There indeed were.

First Arm's-length Clients (1978—)The significance of having a life before translation

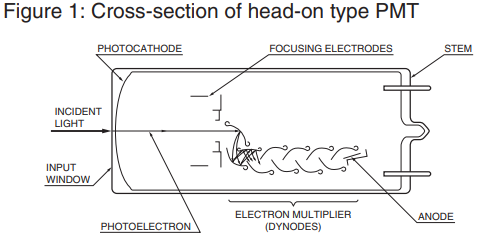

Hamamatsu TV (currently Hamamatsu Photonics) was a customer of mine for measuring instruments, and I took some translation work from them, translating some catalogs and specifications for their photomultipliers, which are special-purpose vacuum tube sensors used to measure extremely low light levels. I don't recall the circumstances surrounding my approach to them (or their approach to me), but it was while I was still serving as the branch manager of the US company.

Hamamatsu TV (currently Hamamatsu Photonics) was a customer of mine for measuring instruments, and I took some translation work from them, translating some catalogs and specifications for their photomultipliers, which are special-purpose vacuum tube sensors used to measure extremely low light levels. I don't recall the circumstances surrounding my approach to them (or their approach to me), but it was while I was still serving as the branch manager of the US company.

After leaving the measuring instrument manufacturer, my next target was the above-noted Japanese measuring and test instrument manufacturer Takeda Riken. They had been a competitor of mine for some products at the time. My initial connection with them was the salesman who had me translate the blood pressure gauge manuals for his new employer. He had formerly worked for Takeda Riken and had introduced me to the founder, who left the company when it was taken over. I had done some interpreting for Takeda Ikuo at meetings and dinners with overseas dealers selling his products.

My still-very-modest career as a technical translator was launched. I added another client, one that made FFT (fast Fourier transform) analyzers, by approaching them with my experience as the branch manager of a company in their general business. That company continued to give me work until the bubble burst for them (and many other places) around 1991–92. In the meantime, I had formed a company, the forerunner of the small company I now operate.

Toward the late 1980s, I received an inexplicable phone call from an attorney in the US. Until then, I had no attorney clients. Uh, what's a deposition? The attorney was coming to Japan to prepare his Japanese client to have some of their employees give testimony in depositions in civil litigation in the US. He wanted to know if I could help as an interpreter in preparing the deponents to give testimony.

Depositions? Sure, I could assist with depositions, I replied confidently. I then sheepishly asked him what a deposition is. The rest is history, and I have spent more time with attorneys and their clients here than is advisable for anyone, although I quickly discovered that there is an undeniable synergy between interpreting in depositions and translation work. There has been some drama over the years in the deposition room, but mostly just stress.

More recently, in late 2018, I became involved with interpreting for 35-plus days (including all weekend days) in a high-profile criminal investigation involving senior foreign executives of a major Japanese corporation. Yes, that one. That was indeed drama, although I cannot, of course, discuss the substance of the case.

And the trip continues.

Disclaimer

Although this and similar pages on this website are directed at translators:

The content of this page and the fact that it was placed on this website must not be taken that the author believes that translation is a promising career path; it certainly is not. Amplification and background has been provided elsewhere.